Atlas Comics presents

THE TOP 100 ARTISTS OF AMERICAN COMIC BOOKS |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Comics' number one "good girl" artist, Matt Baker may be the only man included on this list for his ability to draw "headlights". Cheesecake notwithstanding, Baker was a spectacular stylist, especially on his signature series, Phantom Lady. His covers had enough impact to be singled out in Wertham's Seduction of the Innocent, and create a cult of collectors which has lasted to this day.

SEE: Phantom Lady #17 (cover)

|

|

|

|

| |

For a core of fans who began reading comics in the late 70's or early 80's, John Byrne is a icon. His work on Iron Fist, Fantastic Four, and of course, X-Men cemented his reputation as a trendsetter and the superstar of his era. His early work featured some sharp drawing in the mold of Neal Adams and Jim Aparo, along with solid, well-constructed layouts that followed the classic template of the Marvel masters. He helped create or define characters such as Sabretooth, Wolverine, and Kitty Pride. The quality of his work has declined noticeably since his departure from Marvel in the mid-eighties, however. Stock poses; uninspired, repetitious layouts and sloppy finishes have helped drop him far down from his previously lofty position in the comics hierarchy.

SEE: Uncanny X-Men #137; Iron Fist #15; Fantastic Four #258

|

|

| |

|

| |

Doug Wildey is known to a generation of fans as the man who designed Johnny Quest for television, but his comic book accomplishments are as a western artist par excellence. After two careers, first as a comic artist, then as a designer and storyboard artist, Wildey returned to the industry in the early 80's with Rio, a beautiful, naturalistic series with some of the most breathtaking western imagery ever in comics. This mini-renaissance helped fuel interest in his earlier work, and crystallize his reputation as an outstanding talent.

SEE: "Rio", Eclipse Monthly #1-2; Rio graphic novel

|

|

|

|

| |

Russ Manning is best known for his work on Tarzan in comics and newspapers, but his greatest moment in comics may be his run on Magnus Robot Fighter. A sleek, sharp artist, his work almost appeared to be prepared by stencil, so perfect is it's execution (he seems to have passed this penchant for perfection along to one of his former assistants, Dave Stevens). The leading light at Dell and Gold Key for many years, Russ has suffered a lack of high profile exposure in comic books, but his newspaper strips ("Star Wars" and "Tarzan") have proven him a genius.

SEE: Magnus Robot Fighter #1-21

|

|

|

|

| |

Mix one part Frazetta, two parts Wally Wood, a jigger of Al Williamson, and a dash of Dave Stevens and you've got something like Mark Schultz. Indebted to these masters, but never content just to copy, Schultz has continued improving during his years in the business. He has produced Xenezoic Tales (and its offshoot, Cadillacs and Dinosaurs) as a paean to the things he loves to draw: fast cars, beautiful women, dinosaurs, jungles, and men of adventure. While his work perhaps lacks the divine spark of visual creativity which elevates Wood and Frazetta, his technique often rivals that of his predecessors, no small feat considering their pedigree.

SEE: Xenozoic Tales #1-11

|

|

|

|

| |

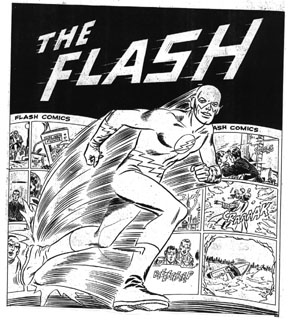

Comicdom may have lost some of Carmine Infantino's best years. An artistic dynamo in the 50's and early 60's, Carmine eventually backed into the role of publisher at DC during some of its most artistically satisfying years. There was a cost, however. His return to the drawing board in the late 70's (after a split with DC) was less than inspiring. Missing was much of what made his earlier work so impressive: sharply designed covers (a job he handled for almost the entire DC line while he was Art Director), nimble drawing, well spotted blacks, and an excellent creative eye. With a hand in the creation or early adventures of characters such as the Flash, Adam Strange, Deadman and many others, Carmine is a major figure in the foundation of modern comics.

SEE: Flash #105-112; Mystery in Space #53-91

|

|

|

|

| |

A solid penciller and a first class finisher, Murphy Anderson strode both sides of the fence for many years at DC. He livened up series such as Hawkman and Mystery in Space with his fine drawing, and as an inker was part of two all-time great art teams with Gil Kane and Carmine Infantino. His precise, delicately feathered rendering worked with equal verve on science fiction, superhero, and mystery books. Many of DC's best remembered books of the 50's and 60's count Murphy Anderson as a chief contributor.

SEE: Mystery in Space #61-64; Hawkman #1-21

|

|

|

|

| |

A devotee of Jack Kirby (who isn't?) Rude is known primarily as the artist/co-creator of Nexus. His figure work is already legendary: tightly defined forms, perfectly delineated foreshortening, expressive facial features, and evocative body language are evidence of a man who has worked hard at his craft. His cartooning skills are equally impressive, making for a unique combination of reality and fantasy, which appears to have influenced artists such as Mike Allred and others.

SEE: Mister Miracle Special #1; Madman/Nexus; World's Finest (mini-series) #1-3

|

|

|

|

| |

With Barry Smith and Jeffrey Jones, Charles Vess completes the triumvirate of comics' most romantic artists. His fine, delicate, almost waiflike style continues in the tradition of the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood of John Millais and Dante Gabriel Rosetti, who also influenced Smith and Jones. Stories of love, heraldry, mythology and fantasy are perfect visual grist for Vess' artistic mill. While his versatility seems to be somewhat limited, he has recognized and exploited this fact by sticking close to subjects and themes which are well served by his talents.

SEE: The Raven Banner graphic novel; Marvel Fanfare #35-37; Sandman #19; Spider-Man: Spirits of the Earth graphic novel

|

|

|

|

| |

Bernie Wrightson's is a somewhat sad story. Fans of his work during the 70's and early 80's will be shocked at his low standing on this list. Others only familiar with his work from the later 80's and beyond, might be surprised to see his name here at all. Bernie's career began the way many energetic youngsters careers begin: with a breathtaking and steadily improving display of sheer technique and chutzpah. His work at Warren, and on DC's Swamp Thing established him as an illustrative star in the mold of Frazetta, Williamson, and Lou Fine, and as the unquestioned heir to the horror mantle of Graham Ingels. Wrightson then took everything he knew about black and white illustration, and embarked on a project which at once cemented his claim to greatness, and drained him of his energy and enthusiasm. Over a period of almost 8 years, Bernie produced scores of highly detailed drawings for an illustrated version of Mary Shelly's Frankenstein. The edition, published in 1983, featured a group of the finest black and white illustrations created since the era of Joseph Clement Coll and Howard Pyle. The effort, however, appears to have been a strain on Wrightson. After a few years away from the business, he returned in the late 80's, and his work, while competent, has never been the same. The responsibilities and pressures of adulthood may obviate a return to the drive and excitement born of youth, but I have a feeling that if Bernie could catch lightning in a bottle once again - look out, we'd really have something on our hands.

SEE: Swamp Thing #7; "The Black Cat", Creepy #103 (rep.); "A Martian Saga", Creepy #87; Creepy #113 (all Wrightson issue)

|

|

Atlas Home | 100 Best Home

Artist Name Index

Numbers 100-91 | Numbers 90-81 | Numbers 80-71 | Numbers 70-61 | Numbers 60-51

Numbers 50-41 | Numbers 40-31 | Numbers 30-21 | Numbers 20-11 | Numbers 10-1

|